When we arrived to Huasco, 855 miles from the Chile-Peru border, we had “only” been in the desert 26 days. It seems like it had been 40 days and 40 nights. We were even seeing things: are those penguins? dog mines? tombs decorated with actual cars?

Someone said there was a “dog mine”. Nate & A imagined a cave full of dogs. We did see more dogs than humans, but a mine of dogs…? Pic: Nate

Hours and hours crossing the desert gave me space to think about important things. For example, I remembered how nice it was to have the nails done, the face dusted off and the skin cleaned. This skin of mine doesn’t like the tropics or the desert. I wetted the towel my Mom gave me and cleaned my face. It felt oh so wonderful, as a warm towel after a looong flight. Water is so scarce here… and we are only a few miles from the ocean.

Chile is divided in regions: first, second, third… to thirteenth −names only a dictator can come up with, said Nate. The driest desert of the world, the Atacama, occupies 41,000 sq miles in the first six regions.

Desert doesn’t look the same everywhere. From the border to Antofagasta, the desert is a ‘mining’ one, rocky, not sandy and with ruins of towns that were while mines existed and now are nothing. Then the desert becomes sandier, with enormous dunes, larger and sporadic rocks and an intense red color. In the southern area of the desert there are cactus, flowers (in October and November) and bushes. Every once in a while there is a fertile valley or a human oasis. Pisagua is one of them.

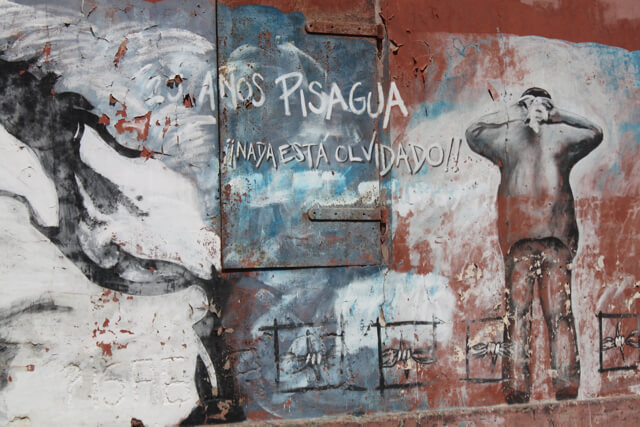

I could live in Pisagua for a while, even though it’s a coastal village, it hardly has water and not one tree around it. Pisagua has history and character. It was first a stop of the Chango nomad people, then it was Peruvian, later burned by the Chileans during the Pacific War and in 1879 rebuilt and converted into an important mining port by its new country. When nitrate mining ended, the rich left and took with them everything they owned, including the economy that moved the town.

They left behind the buildings constructed during the mining boom and that have been falling apart since. There is a clock tower apparently designed by Eiffel, a theater, and a hospital ready for someone to bring them back to life.

It seems like its government is interested in restoring them, now that foreign visitors look interested and its 350 or so residents want the town to flourish, like Marcia, the librarian and key keeper of the Municipal Theater, and Paulina, the paramedic and post officer.

In Pisagua we spent one of those special nights for which any of the possible pains of this trip are worthwhile. We made veggie burritos (a dog stole the meat), Nate played Hurray for the Riff Raff and we looked at the night sky. Amelia met our friend Orion. We saw the Magellanic Clouds, two galaxies outside of ours which can’t be seen in the northern hemisphere.

A few hours from Iquique, we stopped in front of an islet covered with guano. There it was, some 20 meters from us, a penguin colony standing next to hundreds of birds of many different species. They were all sharing the same rock, and I wondered if they had gentrification issues.

We drove by the largest copper open pit mine in the world, crossed rocky and sandy plateaus, and went down a multicolor canyon splattered with salt and bordered by the gigantic Andes to the east. The desert sky is enormous and spectacular 24 hours a day: blue with white brushstrokes, pink with orange spots, and black, completely black, showered with stars like none of us had seen before.

We had heard that atacameños were not particularly hospitable. And we did notice they were not very happy to have us. We also saw why. Their San Pedro de Atacama looks like a disneyland of the desert, where you can no longer find their chañar honey, a dessert they have eaten for centuries. What can be seen are buses of tourists and store after store of tour operators in English and Hebrew. Once again I questioned this invasive tourism that changes the essence of a place and turns it into pretty facades, and nothing else. Benjamin thinks that bus tours have the right to see the Valley of the Moon and its dunes, even if only from the windows.

The hours in the desert have also affected the mood and raised tensions. Nate hasn’t slept well in days. He says he’s looking forward to going back home, to what feels like a home for the first time in many years. I look at the three of them and see my home. I grab onto the minutes left of our trip and see them slip away like sand through my fingers. Van life is all that. It is many things: simple and relaxed, complicated and tiring.

A “normal” day is get up, fold up the bed, take out the table, stove and propane tank, connect them, talk about science, sweep, pack everything back, laugh, turn on the car, fill the tire that’s always low, drive, stop to pee, have lunch on the road, look in the map for the next place to camp, “is there Internet?”, it smells like farts again, charge the phones, “has anyone seen the charger?”, argue, listen to the arguing, arrive to a new campsite, “is it leveled?”, take out the table and stove, connect the propane tank, go for a walk-write-read, watch a movie, halfway sleep almost every night, get up, fold up the bed…

With an advantage: In the last 236 days, many of them spent in the desert, yes, we have explored beaches, forests and steppes. We have seen crescent moons, full moons and waning moons; we have met so many very special people! And we have heard monkeys, vicuñas, flamingos and all the street dogs in Latin America.

We find a place with a view to the ocean and scattered by flowering cactus clumps. Amelia says that she has found a bone trail and that she knows it was rodent and if I had ever seen such a small tooth, no I haven’t. Benjamin walks and thinks the way he does, pacing. And Nate gives me a kiss and writes #homeiswhereyouparkit. The crisis goes away like the dust devil we killed on some road in the desert. Or was it an illusion?

Goosebumps – not the R. L. Stine kind where you’re afraid to open your eyes …. but the OMG I can almost reach out touch what you see kind. Deserts, penguins, joy, frustration, arguments, the heat, the stars, laughter, love … and that always-low tire. Amazing storytelling. Thank you for letting us share your journey. K

Oh Victoria, you can capture a mood, a vision, a state of mind, so well. This trip has to become a book (with pictures of course). Thanks so much for sharing your experience! WB